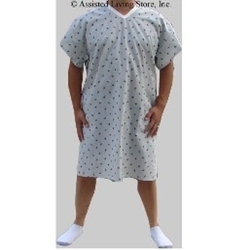

So here we are, Doctor, looking at one another  across the cold space of the exam room. I sit perched in this flimsy gown, socks warming my feet, and we’re about to begin that invisible patient-doctor dance that we both know so well.

across the cold space of the exam room. I sit perched in this flimsy gown, socks warming my feet, and we’re about to begin that invisible patient-doctor dance that we both know so well.

I’m here for the appointment I scheduled as much as two or four weeks ago, when you were recommended by another doctor (or maybe it was a friend or family member). The problem I’m having isn’t a big one, in the great scheme of things, but it’s serious enough that I need a doctor’s attention. And my sitting here provokes some anxiety, a definite fear of the unknown. It’s rather like taking your car to the mechanic for that little rattle in the front end and hoping he doesn’t say you need a whole new engine.

Your front office staff was pretty efficient with the check-in and paperwork, although I didn’t read the privacy notice I signed off on. (I know that by law you have to have me sign, but we all know that this is just a formality. No one really has any privacy anymore, and that’s not just because of the skimpiness of the gowns.)

Your staff was actually warm and friendly, not like some I’ve encountered who seem to think they’re protecting a castle and I’m the peasant knocking at the gate. I didn’t have to stay very long in the waiting room, not even long enough to flip through the new issue of Birds and Blooms I saw on the table. The ease of this whole process means I’ll be much more cooperative now in the exam room. You know how surly we patients can become when we have to wait a long time in a hostile environment. You know we take that surliness out on you.

I could have come sooner if I were willing to see your assistant, but most of us patients aren’t yet accustomed to seeing someone for medical care who doesn’t have an M.D. behind the name. PA, ARNP – all those letters. We don’t know what they mean, and we don’t really want to figure it out.

Because what we truly want is your attention.

So here we are, down to the nitty gritty, me in my gown, you in your white coat, and I should confess that I expect certain things.

First, I want your attention. I need to be acknowledged and welcomed, even though we both know I’d rather not be here. A handshake is good, but mostly, I want to be able to look you in the eye. Speak to me (and whomever I’ve brought with me) directly but kindly, and listen to the story I have to tell, in whatever way I can manage to tell it. Because first of all, I’m a person, not a case.

I prefer to speak with you directly during this appointment, but I know you’re busy and under pressure to see as many patients as you can today. To ease your burden, I don’t mind communicating with your assistants later, as long as all of you give me clear and consistent information with a minimum of bureaucracy. I’d also like to know that I can speak with you directly by phone later if I need more information.

Of course, I want clear information about the problem that brings me here – the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Sometimes it helps to compare my situation to something outside the medical world to help me understand the problem. (This is part of what they call bedside manner.) But if you use an analogy to explain a situation, make it simple and relevant. If I’ve never been a pilot, I won’t understand how the procedure I need is more like flying a 747 than a Piper Cub.

Above all, I am expecting expert care, whether it’s a simple, one-time problem like antibiotics for an infection, or continuing treatment of a chronic illness. If you’re just out of training, I expect that you’ve paid attention to those with more experience. Maybe they’ve been out of school for awhile, maybe you think they’re “old school,” but if they’re still in practice, the odds are great that they’ve learned a lot from experience that you don’t yet have. On the other hand, if you’re many years into your practice, I need to know you’ve kept up with the new approaches and techniques that are actually effective.

By expert care, I don’t mean the most expensive or the latest trend. I just want what will help, and I want you there with me until this problem is resolved. So if that means checking up on me after your treatment, I expect you to do that. After my father had brain surgery a couple years ago, his surgeon never came to his hospital room to see him and had his PA do the follow-up office visit. I’ll tell you straight – that was unforgivable. If a doctor is cutting my head open, I darn well better see that doctor in my hospital room afterward!

Expert care also comes with integrity, a word not often heard these days. (None of those godawful rating websites for doctors even mentions this word.) Integrity hinges on maturity, honesty, and humility. I need to trust that you know what your skills are — and what they aren’t — and that you know your limits and abide by them. So much of medicine and the human body is still a mystery. Despite all you do know, be willing to admit when you don’t have an answer, or when I’d be better off going to see someone else, even if that someone is outside the clinic you work for.

I also need to know that you haven’t been bought – by drug companies, hospital administrators, medical device makers, or anyone else who lures you with the promise of more dollars. These days, everyone talks about health care teams, but the phrase “team player” can be just another term for cronyism. Make sure the team you’re on works for my best interest, not their own egos and incomes. Don’t try to imitate Dr. Oz and be everything to everyone. (You see where that got him!) You get to be known as the best doctor in town not through advertising and marketing, but by doing, day in and day out, excellent work on behalf of your patients. The billboards and bus signs look pretty slick, but word of mouth still reigns.

If I know you have integrity, I can trust you, let down my defenses, and that alone will help me feel better.

Compassion is another word tossed around too lightly by those who don’t understand its true meaning. Compassion is never about you. It’s about whether you’re able to empathize with my situation and help me solve my medical problem. True compassion also demands patience. Listen to my story even though I may not be able to say what I mean or know what questions to ask. Work with me, telling me what to do when necessary, and helping me do what I know I should. Bear with me, even though I may throw up a hundred defenses, and even lie to you about my habits, to protect my ego. And then do your best to offer comfort and reassurance. Don’t give me false hope, but don’t scare me either. Coming to see you means there might be something seriously wrong, and the fear attached to that possibility has increased as I’ve gotten older. I need your reassurance that, whatever comes, you’ll do what you can to help and support.

Unlike some patients, who see you as just a line worker in their personal assembly plant, ultimately what I’m looking for is a relationship with you. A good bedside manner helps, but not to the exclusion of good care and expert skill. Success — for both of us — depends on all these things.

By now you’re likely thinking, geez, this patient expects me to be God, to interpret and meet every need and expectation. And you’re right. We patients expect you to be God, to save us, to never make mistakes, to be always available and ever in control. But then we complain if you act like one. What can I say? Such are the flaws of the human. Is it fair? Nope. Is it true? Very likely.

As I come into your office today, I feel incredibly vulnerable, maybe even frightened. I don’t know if my problem is something minor or something big and scary, and I’m depending on you to help me manage not just the medical problem I have but the anxiety that goes with it.

And that’s all I really want – to feel better, physically, mentally, and emotionally. To feel safe.

You nailed it. In my latest run around looking for a doctor or a PA to fill my prescriptions (as both women who had taken care of me for years, quit just 2 months after I’d seen them last). I got the PA in Austin to write scripts for most of them and a come back in 3 months. But, the joy, the trust I felt once I was back in Dr. Lang’s office was wonderful. And rare. When I see a new doctor, I am in a state of sheer panic for 2 days, have to take a tranquilizer, extra dose, just to leave the house and get to their office. I’ve had several “real” doctors who treated me as you are asking. I miss them terribly and have been adrift since their retirement. But the appointment with the doctor in Ft. Worth allowed me to again be open and honest knowing he was not judgmental, that we are partner’s in my ongoing problems, and, as usual, greeted fully clothed, not rushed. It is a miracle that such doctors still exist. Mostly not–and the patient needs to keep in mind that flimsy paper gown and all, WE have inner power. We can always fire them. We can speak up when they are out of line. It’s hard, but we “hire” them; we are the customer. Still…it’s hard when sick and needing help and understanding and a bit of dignity. Great post.

LikeLike