Not long ago, a friend of mine, having read my earlier posts on how not to choose a doctor, asked how to go about finding a reputable doctor among all the ones out there.

If you’re one of the lucky ones who has insurance coverage and it allows you the freedom to choose your doctor, there are several avenues you can use in the search. These steps apply regardless of whether you have private insurance or are covered by Medicare, Medicaid, your employer or another insurance provider.

First, you’ll need to know which doctors are included in your network of coverage. Though this list won’t indicate which doctor is best for your particular situation, it will help you narrow the field. If your insurance company doesn’t automatically give you a list of physicians, the best way to find it is to contact your insurance company and ask for the list of approved providers. You can do this by mail, email, or phone, and most companies also post their lists in a searchable database on their website.

If you find a number of physicians in the network your insurance covers, consider yourself fortunate. The increasingly narrow networks preclude your having more choice. If you’re in a rural area with sparse medical coverage, are unable to travel far, or have few choices of doctors who accept your insurance, your search, unfortunately, might end right there. But that doesn’t necessarily mean your forced choice will be a bad one. Because of their dedication and purpose, many excellent physicians provide service in small towns and under-served populations, and many of these small clinics are now connected to larger medical centers.

Regardless of the range of choices you do or don’t have, you can still do some research to find out more about the doctor. Once you have your list, try as many of these approaches as you can to get an overall assessment of the physicians you’re considering:

Word of mouth: Despite all our fancy technology, as with any business, word of mouth is still often the best way to find information. Ask around your circle of family, colleagues and friends to see what their experience and recommendations are. As you gather information, take their comments into consideration, with the caveat that their preferences in a doctor might not suit yours.

Some like bold, aggressive doctors; others may like reserved, methodical ones. Some just want a doctor to tell them what to do while others prefer a more collaborative approach. Some think the best doctors are only at large medical centers; others have found very skilled providers at smaller, non-academic centers. (Be wary: a big name on the clinic door does not guarantee a good experience for you. As with people in any profession, there is a range of competency among doctors even in the same practice and bad apples can turn up in prestigious places.) The more you ask around, the more you might find certain names come up again and again as either doctors to see or to avoid.

Talk to other healthcare professionals: Nurses, especially those who work in hospitals, can be a great source of information. Nurses assigned to specific clinics or doctors may need or want to profess loyalty to their fleet of physicians, which can be an inherent bias, although they might be a good source of information if you’re asking about doctors in a different specialty. Nurses who work in hospitals see the outcome of patients from a number of physicians. They’re the ones who see, day in and day out, who has the skills you need. They’ve seen the doctors at their best and their worst, and they know whether a particular physician’s patients generally do well or not.

The category of physicians known as hospitalists – doctors hired by hospitals to attend to patients there — also see the outcome of patients from a variety of doctors and may be willing to give you some guidance. Physician’s assistants (PAs) usually work with or for a particular doctor or group. Like clinic nurses, they may be more objective in making recommendations outside their particular specialty.

If you get the chance to speak with any of these professionals, ask them where they would go for their own treatment and which doctors they would choose.

Check the doctor’s or clinic’s website: These websites can give you important background information, including the doctor’s training and years of experience, special areas of expertise, and philosophy, along with contact and insurance information. Keep in mind, however, that these websites are designed to make all doctors look good. Professional as they appear, they are actually just advertising.

Check the ratings: See what you can find out about the doctor online. The myriad ratings websites like Healthgrades, Vitals and Ratemds can tell you about a particular doctor’s training and certification, specialties and years of experience, along with ratings and comments from patients. Be aware, however, that some of these sites are not up to date and contain errors. If the site doesn’t have a way to screen users, it can also be manipulated by disgruntled patients, and even clinics or hospitals.

What you’re looking for among these sites is consistency of information, so don’t rely on just one of them. Also be aware that these sites often suffer from a glaring imbalance: the people making comments on these sites either love or hate a doctor, with not much commentary in between. Also be aware that patients who complain but later change their minds rarely come back to the site to reconcile the difference. In addition, it’s only the patients who have the time and equipment to register their comments who do so. Thus, the comments you see online might not be a fair representation of the doctor’s skills. On the other hand, by looking at the ratings and reading through the comments on a number of these sites, you’ll be able to pick up any recurring concerns or compliments, which might help you make your decision.

Consider years of experience: Although more experience – in either years or number of cases per year — is generally better, that’s no guarantee a particular doctor is for you. Doctors with more years of experience have likely developed more wisdom and expertise, but should also be keeping up on the latest research and tools in their specialty. A doctor fresh out of residency may have good training and know all the latest tricks, but may lack judgement and skill.

As the American healthcare system has moved more and more to expensive (and perhaps unnecessary) testing and technology, younger physicians have been trained with a different perspective than those in practice a long time. In addition, given the restriction in work hours for residents in recent years, younger physicians may not have as many hours of training and may not be trained as thoroughly in older but still reliable methods. For example, surgeons trained primarily to do laparoscopic surgery may not have equivalent skill doing open procedures when laparoscopic techniques fail.

Consider board certification: Most physicians are certified by the board of their particular specialty (for example, the American Board of Family Medicine), but some are not board certified because of circumstances or choice. For example, physicians just out of training usually have to be in practice for a while before they are eligible for full certification. You’ll see them listed as board-eligible, or BE. Although there is some controversy about the value of it, board certification means that a physician has been vetted by a group of experienced physicians in the same specialty who have assessed whether that physician meets the basic competencies of that specialty. Board certification does NOT, however, guarantee excellence.

Talk to your primary care doctors if you are looking for referral to a specialist: Ask where she or he would go for treatment or where they would send a family member. Be aware, however, that any physician employed by a particular clinic or hospital group might be restricted in referring patients outside that group. Many physicians have been reprimanded or penalized for sending patients to a competing practice, and many hospitals now make it impossible, through the electronic medical records system, for doctors to refer elsewhere.

This is where it’s essential to know your power as a patient. You have the right to ask the doctor whether they’re allowed to refer outside the group. And even if a doctor is prohibited from referring out, you can ask for a referral to a specific doctor of your choice, regardless of whether that doctor is in the referral network of the initial physician. As hospitals and clinics are more and more focused on “patient satisfaction,” it’s important to know what your power as a patient allows you to do in a system that continually restricts what physicians are allowed to do.

Call your state medical society: This is the agency charged with licensing doctors in a particular state. Ask if any complaints have been filed against the doctor you have in mind. Few people know that they can do this, not just for doctors but other categories of state-licensed healthcare providers and even clinics and hospitals. (You can also call them to file a complaint against a provider or state-licensed facility.)

Some states will send you to their online database to check on a doctor, but that database may tell you only if a case against someone has been decided. It will not tell you if there are any cases pending; that information may not be available unless you call the agency directly.

By now you’re probably thinking, geez, this is hard work, and maybe even resent the effort it takes to find someone. Unfortunately, we are in an age of too much information, some of which isn’t trustworthy, and there is too much influence on medical care by business and political forces. These influences mean that you, as the “buyer” of medical care, have to do your research in choosing a physician the same as you would if you were buying a house or car.

If you have other ideas or suggestions that can be used to help patients find good doctors, please add them in the comments section here.

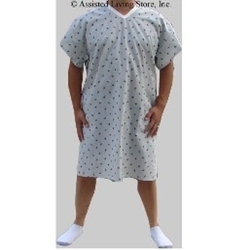

across the cold space of the exam room. I sit perched in this flimsy gown, socks warming my feet, and we’re about to begin that invisible patient-doctor dance that we both know so well.

across the cold space of the exam room. I sit perched in this flimsy gown, socks warming my feet, and we’re about to begin that invisible patient-doctor dance that we both know so well.